Savannah’s documented history dates back to 1733, when General James Oglethorpe and 120 passengers aboard the ship Anne landed on a bluff overlooking the Savannah River in February. Oglethorpe named the colony “Georgia” in honor of King George II of England, and Savannah proudly became the first city of this new territory.

After settling, Oglethorpe formed a friendship with Tomochichi, the local Yamacraw Indian chief. The two pledged mutual goodwill, and Tomochichi granted permission for the settlers to establish Savannah on the bluff. Thanks to this peaceful alliance, the town prospered without the warfare and hardships that plagued many other early American colonies.

During the American Revolution, the British captured Savannah in 1778 and maintained control until 1782. In 1779, a combined French and American force attempted to reclaim the city through a siege followed by a direct assault, but their efforts were unsuccessful.

After gaining independence, Savannah prospered. Farmers soon realized that the fertile soil and favorable climate were ideal for growing cotton and rice. Plantations and slavery became highly profitable in the neighboring South Carolina Lowcountry, leading Georgia—the formerly free colony—to legalize slavery as well.

Savannah was not immune to hardship. Two major fires in 1796 and 1820 each reduced half the city to ashes, but the residents rebuilt each time. In 1820, a yellow fever outbreak claimed the lives of one-tenth of the population. Despite facing fires, epidemics, and hurricanes, Savannah consistently showed resilience and bounced back stronger.

Before the Civil War, Savannah was celebrated as America’s most picturesque and peaceful city. Renowned for its majestic oak trees draped with Spanish moss and its refined residents, the city embodied Southern charm. During this era, the Georgia Historical Society was established, and the stunning Forsyth Park gained its iconic ornate fountain—a must-see landmark.

At the dawn of the 20th century, cotton once again reigned supreme. Savannah prospered alongside emerging industries such as resin and lumber exports. However, the arrival of the boll weevil devastated much of the cotton crop and the state’s economy, coinciding closely with the onset of the Great Depression.

Historic River Street, paved with cobblestones over 200 years old, stretches along the Savannah River’s edge. Once bustling with warehouses storing King Cotton, the area never fully rebounded after the 1818 yellow fever epidemic and quarantine. Abandoned for more than a century, River Street was rediscovered in the 1970s by local landowners and urban planners dedicated to restoring its rich history and former grandeur.

In June 1977, Savannah unveiled a revitalized waterfront at a cost of $7 million. Approximately 80,000 square feet of vacant, abandoned warehouse space was transformed into a vibrant mix of shops, restaurants, and art galleries.

But there is more to do here than just shop and eat. Be sure to take a stroll along the lovely landscaped river walk that runs between River Street and the Savannah River, where you’ll find Savannah’s Waving Girl and the Olympic Cauldron monument. Then explore the bluffs along the river on the old passageway of alleys, cobblestone walkways, and bridges known as Factors Walk.

River Street stretches east to west along the Savannah River and served as the primary route for traffic and goods entering Savannah throughout the 1700s and much of the 1800s. The port located on River Street was a key driver of Savannah’s economic growth during that era. Throughout its history, the riverfront has remained vital to Georgia, functioning as a colonial port, a cotton export hub, and now a popular tourist destination.

Significant buildings that were saved and restored include:

- The Pirates’ House (1754), an inn mentioned in Robert Louis Stevenson’s book “Treasure Island”; the Herb House (1734), oldest building in Georgia; and the The Olde Pink House (1789), site of Georgia’s first bank.

- The birthplace of Juliette Gordon Low (completed in 1821) now owned and operated by the Girl Scouts of the U.S.A. as a memorial to their founder.

- The Telfair Academy of Arts and Sciences, built in 1812 as a mansion, was one of the South’s first public museums.

- Restored churches include: The Lutheran Church of the Ascension (1741); Independent Presbyterian Church (1890) and the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist (1876), one of the largest Roman Catholic churches in the South.

- The First African Baptist Church was established in 1788.

- Savannah’s Temple Mickeve Israel is the third oldest synagogue in America.

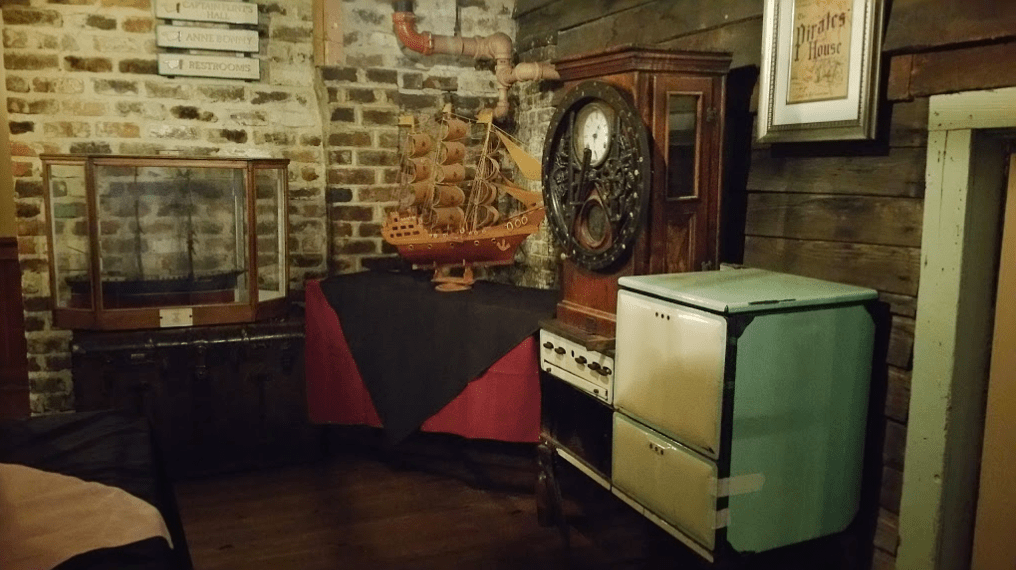

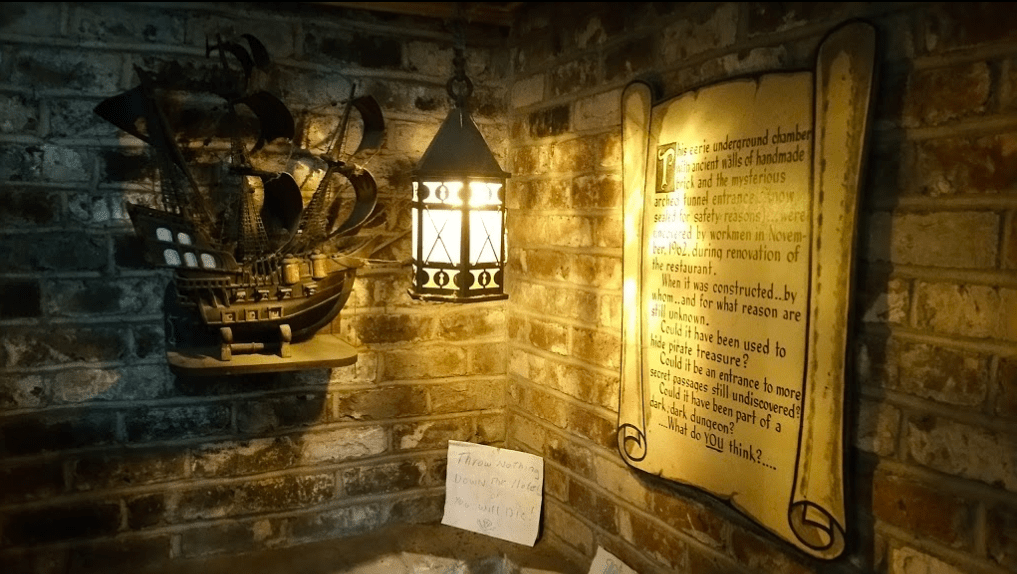

The Pirates’ House is a historic seaman’s tavern, believed to have been built in 1794. Just a block from the Savannah River, it was a favored gathering spot for sailors—and pirates. Legend has it that sea captains often shanghaied unsuspecting sailors right from the tavern, drugging drunken men and whisking them away to mysterious ships bound for unknown destinations.

By 1753, as Georgia grew firmly established and the experimental garden was no longer needed, the site was transformed into a residential area. Savannah, now a bustling seaport, saw one of the first buildings on the former garden grounds become an inn catering to visiting sailors. Just a block from the Savannah River, this inn quickly became a favored haunt for fierce pirates and sailors from across the Seven Seas. Here, they drank fiery grog and swapped tales of their adventures—from Singapore to Shanghai, and from San Francisco to Port Said.

These historic buildings have recently been transformed into one of America’s most distinctive restaurants: The Pirates’ House. While equipped with all the modern amenities, the restaurant has thoughtfully preserved the authentic atmosphere of those thrilling days of wooden ships and iron-willed sailors.

In the Captain’s Room and The Treasure Room, framed pages from a rare early edition of Treasure Island hang on the walls. The tavern gained fame through Robert Louis Stevenson’s classic novel, where Captain Flint is said to have died in an upstairs room, shouting his final words, “Darby, bring aft the rum.” The story’s infamous Long John Silver claims, “I was with Flint when he died at Savannah.”

In the Captain’s Room, with its hand-hewn ceiling beams joined by wooden pegs, shorthanded shipmasters secretly negotiated to shanghai unsuspecting seamen to fill their crews. Legends tell of a tunnel running from the Old Rum Cellar beneath the Captain’s Room all the way to the river, used to carry these drugged and unconscious men to waiting ships in the harbor. Many a sailor, drinking freely at The Pirates’ House, awoke to find himself aboard a strange vessel bound for a distant port halfway across the world. According to local lore, a Savannah policeman once stopped by for a friendly drink, only to wake later on a four-masted schooner sailing to China—and it took him two years to return home.

GHOST STORIES

Savannah was strategically founded on high ground, chosen for its natural defensive advantage—a bluff offering protection from waterborne attacks. This key factor influenced General Oglethorpe’s decision to establish the city at this site. What he may not have known—or perhaps overlooked—is that the area also served as a burial ground for several Native American tribes. At the base of the bluff lies River Street, where docks were constructed that played a pivotal role in shaping global economies through the export of cotton—and the tragic importation of enslaved people. Cotton and other goods were shipped out, while slaves were brought in, marking a complex and painful chapter in Savannah’s history.

While workers hurried day and night to load outgoing ships with goods and products, incoming vessels also arrived to unload their cargo. For nearly a century, that cargo tragically included human beings—enslaved people bound in chains and metal. For them, this was not a land of freedom or opportunity, but one of cruelty, heartbreak, and shattered dreams. After being unloaded from the ships, these enslaved individuals were brought into the warehouses along River Street, often under the cover of darkness to conceal their dire condition from potential buyers. Imprisoned within these warehouses, they were kept until ready for sale, when they were led out the back, through the Factors’ Walk area, and beneath Bay Street via tunnels into the basements of buildings up and down the street. Many never left the confines of the River Street buildings, succumbing to disease, despair, and exhaustion—their fragile bodies unable to endure another day of loss and sorrow. Even today, remnants of shackles remain embedded in some of the buildings along River and Bay Streets, silent witnesses to this dark chapter in history.

The enslaved people brought to Savannah not only played a crucial role in building the city’s prosperity but also left a lasting mark on its haunted legacy. Many of the buildings along River Street once served as holding places for slaves after their grueling journey from Africa. It’s chilling to imagine the horrors that unfolded within those walls. The sorrow and suffering endured by these individuals have left an enduring, heavy energy that still casts a dark shadow over many spots on River Street today.

Take your chances and stay at a converted cotton warehouse where a lot of these slaves perished. The River Street Inn’s original two floors, built in 1817 out of recycled ballast stone, were soon inadequate to house the increasing amount of cotton moving through the port. As the building has the Savannah River to the north and a high bluff to the south, with buildings on either side, the only way to expand was to go higher.

Similar to many of the buildings along the river, the original structure of the hotel was built for the storage, sampling, grading, and export of raw cotton. By early in the 19th century, Savannah was the world’s second largest cotton seaport, due in large part by the invention of the cotton gin.

Factor’s Walk

To facilitate the storage and removal of large cotton bales, each level required outside access, leading to the creation of a network of alleys and walkways along the bluff. These passageways became known as “Factor’s Walk,” named after the cotton graders who worked there. Today, these alleys contribute to the distinctive character and historic charm of the hotel. Additionally, many of the riverside streets and nearby buildings are constructed from ballast stone—originally used as ballast in the ships that sailed to Savannah from ports around the world.

The cobblestone street would make it difficult for a wheelchair, scooter, or stroller. The walking path along the river is smooth, and small portions of the street are smooth, but most of the street is cobblestone (actually ballast from early sailing ships).

The lower floors feature wide, arched doorways designed to facilitate the movement of large cotton bales. In 1853, three additional floors were added: the third floor for extra storage, and the fourth and fifth floors for office space. Because the upper levels served as offices, they were equipped with floor-to-ceiling windows to maximize natural light, fireplaces for warmth, and—most notably—balconies that allowed the factors to oversee the arrival, departure, loading, and unloading of cargo ships.

After the Civil War, as cotton prices sharply declined, Savannah’s cotton warehouses gradually fell out of use. The building that now houses the River Street Inn served as a warehouse for various shipping companies until its redevelopment in 1987. In 1998, the inn expanded beyond its original 44-room structure into the neighboring building, growing to its current size of 86 rooms.

Savannah’s Historic District was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1966. It is one of the largest historic landmarks in the country.