This is a place steeped in rich, layered history—one of those unmistakably Southern landscapes shaped by Native American roots, African heritage, and European settlement. The ruins lie nestled within a diverse ecosystem beside a major river that once sustained a thriving town, a booming textile industry, fertile farmland, and a spirited, singular community.

Hernando de Soto’s expedition entered the region in April 1540, spending just a few days along the middle Oconee River within the territory of the Paramount Chiefdom of Ocute before heading east toward South Carolina. While there’s no direct evidence that de Soto himself visited Scull Shoals, he was certainly in the vicinity, moving through nearby Native towns. His force—comprising soldiers, horses, war dogs, and enslaved bearers—quickly depleted the local food stores. More tragically, the Spaniards left behind deadly diseases like smallpox, plague, and influenza, to which the Native population had no immunity. The result was a catastrophic decline in the Indigenous population.

Scull Shoals began as a frontier settlement in 1782 and grew rapidly after the 1802 treaty opened lands west of the Oconee River to settlers. White settlers and enslaved Black laborers quickly cleared and cultivated the land. The community first established a gristmill and sawmill, and after Eli Whitney’s invention of the cotton gin in 1793, cotton production took off—transforming Scull Shoals into a thriving agricultural and industrial hub.

Under the ownership of Dr. Thomas M. Poullain, Scull Shoals evolved into a bustling industrial village, home to gristmills, sawmills, a four-story brick textile mill, general stores, and residences. At its peak, the mill employed around 500 workers who operated 4,000 spindles. Dr. Lindsay Durham, a prominent local figure, cultivated an extensive herb garden and ran a sanatorium, developing and distributing medicinal remedies. However, repeated flooding in the 1880s led to the mills’ decline, and by the 1920s, the once-thriving town had been completely abandoned.

The devastating flood of 1887 left water standing in the buildings at Scull Shoals for four days. The covered toll bridge was swept away, several hundred bales of cotton were ruined in the mill, and 600 bushels of wheat spoiled in the warehouse. The damage brought economic collapse to Scull Shoals Mills—one from which the town would never recover. What remains today is the ghost of a once-thriving community and the remnants of lives altered by nature’s destructive force. Not long after the flood, the town’s final resident moved on, and Scull Shoals faded into obscurity… but not entirely.

Scull Shoals became part of the newly created Oconee National Forest in 1959. The old mill town has laid quietly waiting, marked only by the ruins in the woods. Now the 2,200 acre experimental forest area, contains the mill town, and a prehistoric mound complex dating from A.D. 1250-1500.

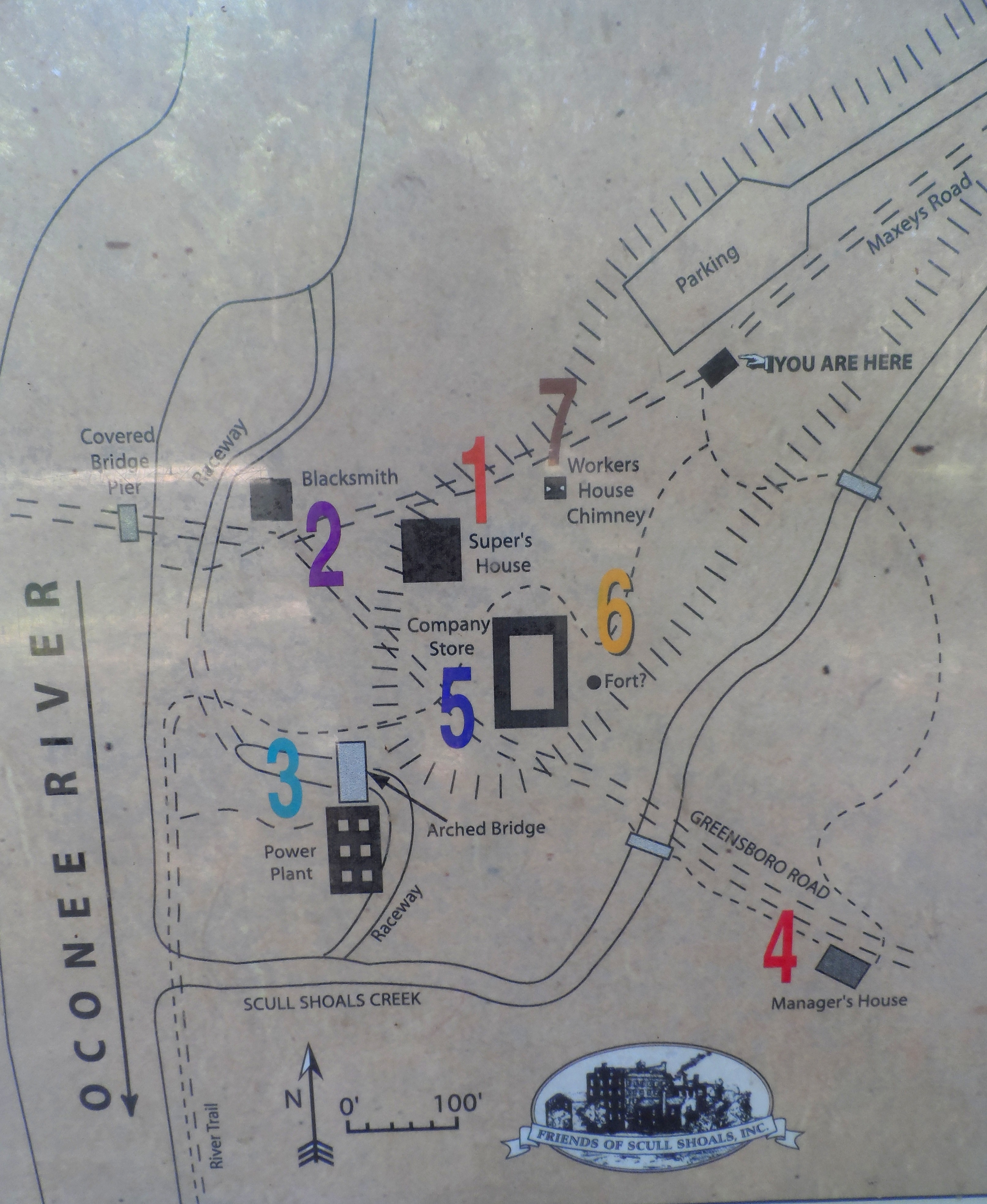

Today, only three brick walls of the old warehouse and store still stand, along with the arched brick bridge that once carried workers across the raceway into the mills. In the heart of the former village and scattered throughout the surrounding woods, you can find stone foundations from the mill’s power plant and remnants of brick and stone chimneys. From the banks of the Oconee River, traces of the wooden covered toll bridge can still be seen—faint echoes of a town long past.

The crumbling ruins of Scull Shoals possess a haunting beauty, standing as a solemn tribute to the town’s former residents—including those who were ultimately forced to leave their homes behind.

The Scull Shoals Mill ruins are located halfway between Athens and Greensboro, on the Oconee River. Just northeast of where Georgia State Route 15 crosses the river.